Cognitive Overload: When Your Brain Reaches Its Limit

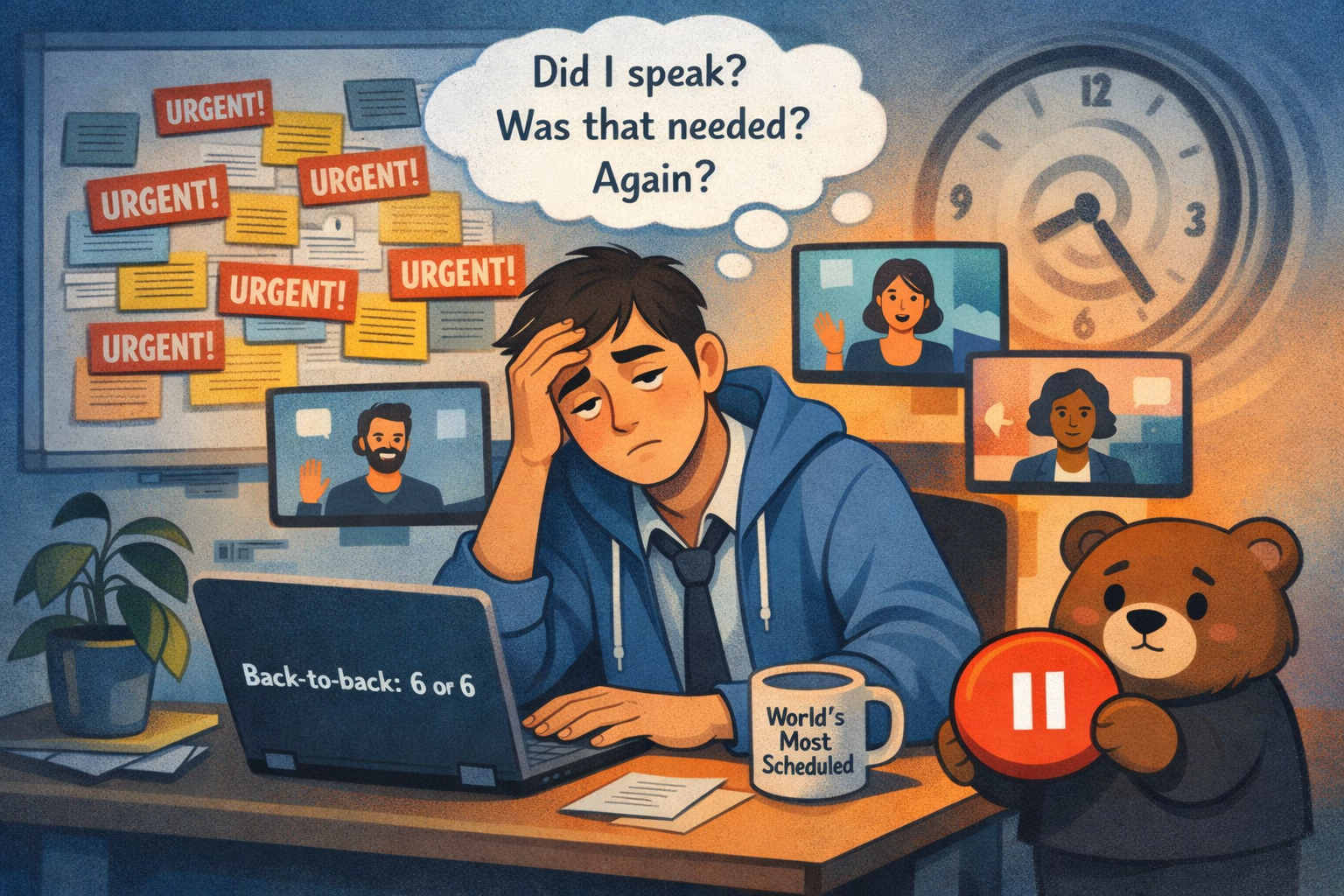

Meeting overload isn’t a character flaw or a “time management problem.” It’s a form of cumulative cognitive fatigue that builds when your day asks for repeated context switching, sustained attention, and ongoing social evaluation—often without enough space for your mind to complete what it started.

Have you ever finished a full day of meetings and felt both busy and oddly directionless?

That experience can be deeply disorienting because it looks, from the outside, like you were “working all day.” But internally, your attention systems may have been running a continuous coordination loop: track people, track status, track next steps, track what you’re supposed to say—and then move on before anything fully settles.

After a meeting-heavy day, many people describe a particular kind of tired: not sleepy, not physically exhausted—more like foggy, saturated, and slightly brittle. Your brain can feel packed with fragments: half-decisions, open questions, names, tone shifts, and obligations that never got a clean ending.

This is why meeting overload can feel so unfair. You may have been attentive, responsive, even helpful—and still end the day with low clarity and reduced capacity for anything that requires sustained thought. That drained “busy but unproductive” state is a recognizable cognitive load pattern, especially when meetings are frequent or back-to-back. [Ref-1]

Deep focus depends on continuity: you hold a problem in mind, build a map, test options, and gradually reduce uncertainty until there’s a stable “done” signal. Meetings tend to interrupt that cycle. Each one asks your attention to drop one map and pick up another—new topic, new goals, new constraints, new personalities.

Working memory is not built for carrying ten partially-open loops at once. When meetings stack, the brain starts prioritizing short-term tracking over long-horizon thinking: remembering what was said, what needs follow-up, and what might be expected next. That’s not a moral failure; it’s what attention systems do when continuity is repeatedly broken. [Ref-2]

In human history, being attuned to group dynamics wasn’t optional. Tracking inclusion, hierarchy, disagreement, and alliance was a safety function. Modern meetings—especially video meetings—activate many of the same monitoring systems: Who’s watching? Who agrees? Did I signal competence? Did I miss something?

That continuous social attention is costly because it keeps the brain scanning while also trying to process content. Even when nothing “bad” happens, the body can stay in a subtle state of readiness: interpret micro-signals, time your turn, manage impression, anticipate next moves. Over hours, that becomes fatigue you can’t always name. [Ref-3]

You can leave a meeting with nothing urgent on paper, yet still feel like your system never stood down.

Meetings don’t only drain; they also provide a kind of short-term stability. When work is ambiguous, roles are shifting, or priorities keep changing, a meeting can function like a brief “safety cue”: visibility, shared reality, and the sense that people are aligned—at least for the moment.

This is one reason meeting-heavy cultures persist. A meeting can create a temporary feeling of control: we talked, we checked in, we’re on it. But reassurance is not the same as completion. When the meeting ends without clear closure—ownership, decisions, or a settled direction—the nervous system often stays activated, holding the uncertainty for later. [Ref-4]

There’s a common illusion in modern work: if we’re meeting often, we must be coordinated. But coordination takes energy, and execution takes uninterrupted capacity. When meetings consume most of the day, alignment becomes something you perform repeatedly instead of something that stabilizes into action.

Video calls can intensify this. The constant close-up attention, limited movement, and heightened self-monitoring can amplify cognitive load, making it harder to transition from “being perceived” into “building something.” The result is a paradox: the more you meet to ensure progress, the less cognitive bandwidth remains to create it. [Ref-5]

In many workplaces, meetings become a Power Loop: a self-reinforcing cycle where visibility and control start to matter more than outcomes. When uncertainty rises, the system reaches for what it can measure immediately—attendance, updates, responsiveness—because those signals are fast and socially legible.

Over time, the calendar becomes a proof of engagement. The cost is subtle: attention gets spent on staying in the loop rather than completing loops. People feel pressured to be present, quick, and agreeable—while their deeper thinking and follow-through get pushed into thinner and thinner margins. Meeting fatigue and “Zoom fatigue” are common expressions of this load. [Ref-6]

What if the exhaustion isn’t from work itself, but from never reaching a clean end-point?

Meeting overload tends to show up less as one dramatic symptom and more as a pattern of small degradations—signals that cognitive resources are being used for tracking and social navigation rather than synthesis.

These are not personality traits. They’re often what happens when working memory is saturated and completion signals are repeatedly deferred. [Ref-7]

Creativity and complex problem-solving rely on sustained, self-directed attention. They require enough internal space to hold a question long enough for structure to emerge. Chronic meeting load reduces that space. Your day becomes externally paced: respond, attend, update, adjust.

Over time, this can shrink the felt sense of autonomy—not because you “don’t care,” but because your attention rarely belongs to you long enough to develop momentum. Even when you have good ideas, the system may not have the capacity to carry them to completion. Executive function depletion and decision fatigue are common in this environment, especially when meetings are frequent and evaluative. [Ref-8]

Meeting proliferation often has less to do with collaboration and more to do with social risk management. In hierarchical or uncertain environments, being seen can feel protective. Showing up signals loyalty, competence, and inclusion. And when exclusion feels costly, people default to more touchpoints, more check-ins, more “just to be safe” alignment.

This is not simply “fear” in a psychological sense; it’s structural. When outcomes are hard to measure and consequences are unclear, visibility becomes a substitute metric. Virtual settings can intensify this dynamic by increasing cognitive and attentional strain while also making social signals harder to read, which can prompt even more meetings to compensate. [Ref-9]

Sometimes meetings aren’t where work happens. They’re where belonging gets confirmed.

There’s a distinct difference between “having time” and having a coherent stretch of time. Uninterrupted focus blocks support cognitive rhythm: you can stay with one problem long enough to reduce ambiguity, make a decision, and reach a natural stopping point. That stopping point matters. It’s one of the ways the nervous system receives a stand-down signal.

When fatigue is high, people also become more likely to conform in group settings—agreeing quickly, avoiding complexity, and moving on—because cognitive control is taxed. In that context, focus time isn’t a luxury; it’s a condition that supports clearer thinking and more reliable judgment. [Ref-10]

This isn’t about insight or better intentions. It’s about what becomes possible when attention isn’t repeatedly torn away before it can land.

Meeting-heavy cultures often develop when ownership is diffuse and trust is thin. If it’s unclear who decides, who executes, or how progress is verified, the group compensates with more real-time coordination. Meetings become a container for uncertainty.

By contrast, when ownership is explicit and information can travel without everyone being present at once, the system doesn’t need as much live syncing. This is partly neurological: constant virtual attention taxes the same attentional networks again and again, while asynchronous clarity can reduce repeated social monitoring. [Ref-11]

When roles are clear, fewer conversations are needed to feel safe inside the work.

As meeting load decreases—or becomes more purposeful—many people notice a specific shift: thinking deepens. Not because they “try harder,” but because mental energy stops leaking into perpetual context reloading. Working memory is freed to build models, connect information, and carry tasks to completion.

Coherence is the felt experience of fewer open loops and more settled ones. You can remember what matters without forcing it. Priorities separate naturally. The day has chapters instead of fragments. When cognitive load drops closer to the brain’s limits, clarity returns as a byproduct of restored capacity, not as a motivational achievement. [Ref-12]

Healthy collaboration doesn’t require continuous contact. It requires shared outcomes, reliable handoffs, and moments of real alignment that produce closure—decisions made, responsibilities held, and information placed where it can be retrieved without re-litigating it live.

When meetings are redesigned around outcomes, they stop being default containers for uncertainty. They become discrete events with a beginning and an end—supporting execution rather than replacing it. This also reduces context switching, which is one of the quiet drivers of fatigue and diminished focus across a workday. [Ref-13]

It can help to see meetings for what they are: one coordination tool among many, not a moral requirement and not the default shape of work. When meetings become automatic, they often function as a control substitute—something that briefly reduces uncertainty without producing completion.

As soon as the calendar is carrying more coordination than the mind can metabolize, fatigue is not a personal deficit; it’s a predictable outcome of fragmentation. In environments where attention is repeatedly split, agency tends to reappear when work regains clearer edges—fewer switches, fewer open loops, more genuine endpoints. [Ref-14]

Your attention is not an infinite resource, and cognitive fatigue is not a sign that you’re “not built for work.” It’s often a sign that your mind has been asked to hold too many partial threads without enough uninterrupted space to tie them off.

When there is room for completion, meaning can form in a very practical way: the work becomes legible, identity feels less performative, and progress registers internally as real. Not louder. Not more optimized. Just more settled—because fewer parts of you are still waiting for the day to finish. [Ref-15]

From theory to practice — meaning forms when insight meets action.

From Science to Art.

Understanding explains what is happening. Art allows you to feel it—without fixing, judging, or naming. Pause here. Let the images work quietly. Sometimes meaning settles before words do.