Habit Coaching: Why Accountability Changes Everything

Many wellness programs look solid on paper: a plan, a schedule, a streak counter, a coach, a curriculum. And yet, plenty of people have the same confusing experience—starting strong, fading out, restarting, and wondering what’s “wrong” with them.

What if the problem isn’t willpower, but a mismatch between structure and meaning?

From a nervous-system perspective, long-term change usually stabilizes when life feels more coherent: your actions create “done” signals, the load drops, and what you’re doing starts to belong to your identity instead of hovering outside you as another task. Programs can help—but not because they pressure you. They help when they organize attention and accountability in a way that can actually settle into who you are.

A program can be well-designed and still feel oddly frictional—like it’s happening to you rather than with you. That experience is common in modern life, where people are already carrying heavy cognitive and emotional load. Under load, even positive changes can register as more demand.

Often the issue isn’t that you don’t care. It’s that the program doesn’t create enough internal closure to justify the effort. You complete sessions, but the day-to-day story of “this is me” doesn’t update. When identity doesn’t get a clean signal, your system treats the program like an external appointment—easy to miss when life gets busy.

In other words: the program may offer improvement, but it may not offer belonging. And without belonging, participation becomes something you must repeatedly re-choose under pressure—an unstable setup for most nervous systems. [Ref-1]

Structure is often misunderstood as rigidity. Biologically, good structure is more like scaffolding: it stabilizes attention and reduces decision fatigue so your system can stop renegotiating the basics each day.

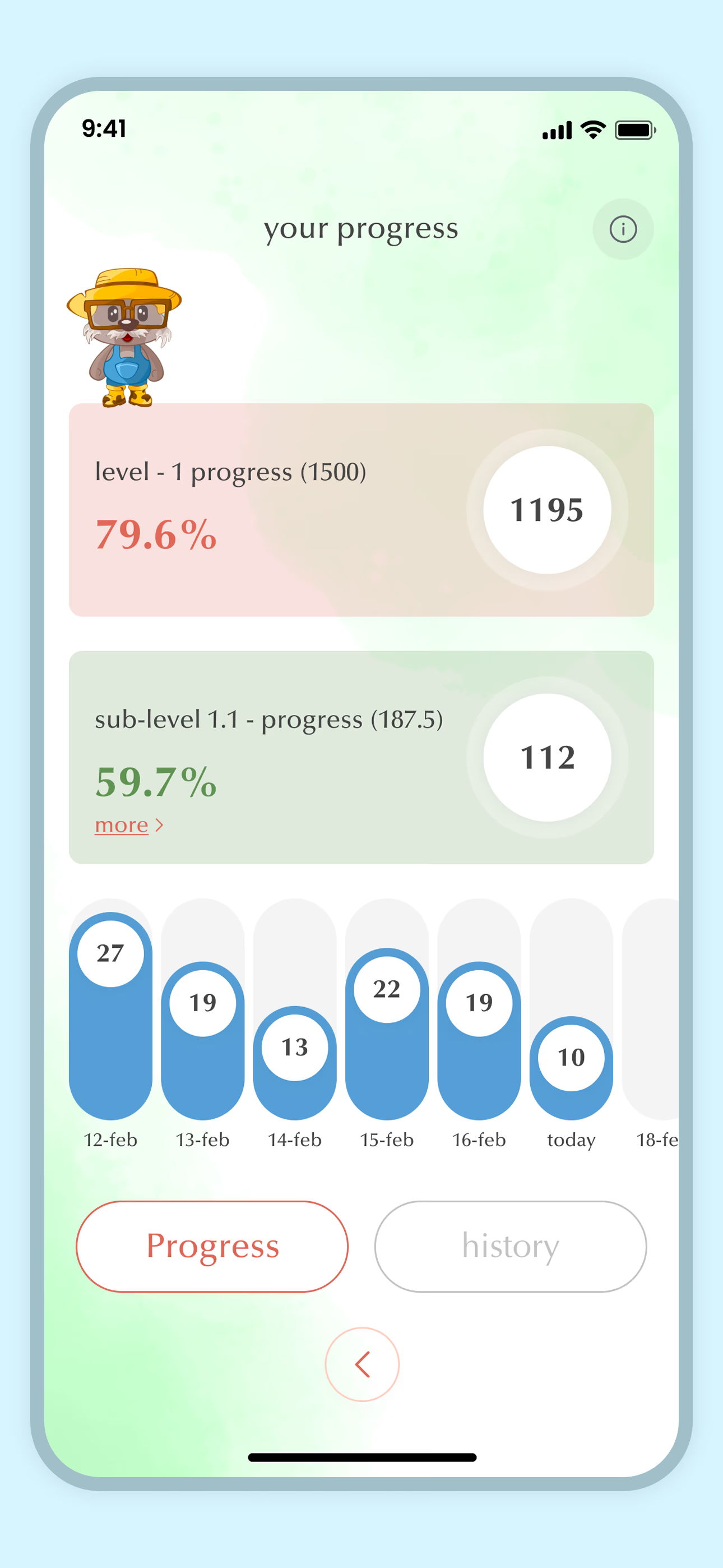

When a program reliably answers “what happens next,” it can lower background uncertainty. Feedback loops (check-ins, reflection prompts, progress markers) also help the brain connect actions to outcomes—an important ingredient for behavior to become self-reinforcing instead of effort-driven. [Ref-2]

Over time, consistent structure can make the experience feel less like self-control and more like continuity. That continuity is where identity-level change begins to have a place to form—not as an insight, but as a repeated completion signal your body can recognize.

Habit language is helpful, but incomplete. Humans are also narrative organisms: we regulate through meaning, roles, and a sense of “what kind of life this is.” A wellness program becomes easier to sustain when it plugs into that narrative system—when it helps you inhabit a clearer self-concept, not merely perform a routine.

This is one reason motivation swings so dramatically. Motivation is often treated as a personal resource, but it’s also a coherence signal. When the program aligns with your values and self-direction, your system experiences more autonomy and less internal drag. When it doesn’t, participation can feel like compliance—even if you chose it. [Ref-3]

Notice the distinction: understanding your values is not the same as integration. Integration shows up later, when the repeated pattern feels like a settled part of “how I live,” not a recurring project you must keep persuading yourself to do.

Accountability gets a mixed reputation because it can feel like pressure. But at its best, accountability is a stabilizer: it reduces ambiguity, creates predictable touchpoints, and helps actions feel consequential in a clean, bounded way.

When guidance is delivered with respect for autonomy and capacity, it can function as a safety cue: “You don’t have to hold this alone; the pathway is held.” That tends to lower nervous-system noise and make follow-through more available. [Ref-4]

Programs that offer structure without shame also help people recover a basic sense of orientation—what matters, what’s optional, what’s next. Under stress, orientation is regulation.

Many programs are built around endpoints: 14 days, 8 weeks, a challenge, a streak. Endpoints are not inherently bad—they create containers. The mismatch happens when the endpoint is treated as the thing that produces change.

Long-term change tends to depend less on finishing and more on whether the program helped your system internalize a new pattern as meaningful and self-relevant. If the experience never becomes identity-consistent, the nervous system files it as temporary exertion—something you did, not something you are.

Group-based formats often succeed not because “people try harder,” but because they create shared context, repeated closure, and a sense that the change belongs in real life rather than in an isolated sprint. [Ref-5]

A program can be understood as a loop: you show up, you do a bounded action, you get feedback, you re-enter life slightly reoriented. When the loop is well-designed, it doesn’t only stimulate you into activity—it helps the experience complete.

Completion matters because completion is what allows stand-down. Without it, people can stay in a low-grade “not done yet” state—constantly restarting, re-committing, and re-evaluating. A Meaning Loop reduces that churn by repeatedly connecting effort to coherence: “This fits. This counts. This is part of me.”

Online and group-based programs can support this loop by making participation visible, socially grounded, and easier to return to after disruptions—less like a personal battle, more like a shared rhythm. [Ref-6]

Because modern wellness culture often confuses intensity with effectiveness, it can help to name quieter indicators of integration. These signals aren’t about feeling “more inspired.” They’re about how stable the pattern becomes under real-world variability.

These are not moral achievements. They’re signs that the loop is closing often enough for your system to trust it.

If a program is disconnected from identity, it can still produce short bursts of motivation—especially if it’s novel, gamified, or socially visible. But motivation without belonging tends to decay. The structure remains external, and your nervous system treats it as optional under load.

In that situation, “falling off” isn’t a character flaw. It’s a predictable response to a loop that never fully closes: actions happen, but the internal narrative doesn’t consolidate. Without consolidation, the consequences feel muted, and returning requires another surge.

Some people then become dependent on external guidance to re-enter the loop—always looking for the next program to re-create urgency. Identity-informed design (including shared social identity) is one way programs reduce this dependency by making the change feel more like membership than compliance. [Ref-8]

When the structure holds but the meaning doesn’t land, the effort can feel oddly disposable.

Tracking and milestones can be either regulating or destabilizing. When they communicate “you’re oriented, you’re in process, you’re not alone,” they strengthen continuity. They help attention return to the same thread, which is one of the simplest ways modern fragmentation gets repaired.

In combined models—like app support plus group support—people often do better not because the app is magic, but because the intervention supplies repeated re-orientation: the same values, the same language, the same social context. That repetition is how identity takes shape over time. [Ref-9]

Accountability also works structurally: it makes the loop more complete. “Someone will notice” is not just pressure; it’s consequence clarity, which helps behavior feel real enough to settle.

At a certain point, the most important shift isn’t that you “want it more.” It’s that the behavior requires less mobilization. You still have stress, distraction, and imperfect days—but the baseline becomes more stable.

This is where people often describe feeling more self-regulated: not as a mood, but as increased capacity to return to signals. The practice begins to function like a home base. Instead of the program constantly pushing you forward, it starts creating a quieter sense of internal order.

Evidence from workplace and real-world wellness initiatives suggests outcomes are mixed when engagement is low, but more meaningful when participation is sustained and supported by context. That fits the nervous-system view: stability is an emergent property of repeated, completed loops—not a one-time burst of effort. [Ref-10]

What changes when a program becomes “part of me,” rather than “something I’m doing”?

Humans regulate in groups. Not as a sentimental idea, but as biology: shared rhythms, shared language, and shared expectations reduce uncertainty and provide safety cues. This is one reason mentorship, peer groups, and community features can dramatically change a program’s impact.

When the culture around you reinforces the same orientation, the program stops being a private struggle and becomes a shared standard. That can lower the nervous-system cost of maintaining the pattern—less self-monitoring, less isolation, fewer restarts. [Ref-11]

Leadership modeling and supportive norms matter here, too, because they signal whether wellness is a genuine value in the environment or an individual performance metric.

People often imagine intrinsic motivation as constant enthusiasm. In practice, it can look much quieter: fewer dramatic recommitments, fewer guilt spirals, and more steady follow-through because the behavior feels self-consistent.

When a program is internalized, the person doesn’t rely as heavily on external prompts to remember what matters. The orientation becomes portable. You can be in a different week, a different season, even a different level of energy—and still recognize the same thread.

Many wellness programs emphasize ongoing engagement and personalization for this reason: not to keep people hooked, but to keep the experience relevant enough that it continues to “fit” as life changes. [Ref-12]

The most sustainable outcome is not permanent dependence on a platform, coach, or challenge. It’s when the scaffolding has done its job: the person can generate the structure in smaller, self-directed ways because the identity-level orientation is now established.

This doesn’t mean life becomes perfectly consistent. It means disruptions don’t erase the narrative. A missed week is no longer evidence of failure; it’s a normal fluctuation in load, followed by return—because return is part of who you are.

Programs that stay effective over time often invite participant voice and ownership and evolve with real feedback. That adaptability helps the structure remain humane and identity-aligned rather than becoming another rigid demand. [Ref-13]

A wellness program is easiest to evaluate through a dignity-based lens: does it reduce noise, clarify what matters, and help your actions feel like they belong to your life? If yes, it’s not just tracking behavior—it’s supporting coherence.

In a fragmented environment, scaffolds can be profoundly supportive. But the scaffold isn’t the house. Long-term change tends to emerge when the structure helps experiences complete often enough that your nervous system can stand down—and your identity can update in a stable way.

Many workplace and digital wellness frameworks increasingly emphasize values alignment, leadership support, and multiple domains of well-being, which reflects this broader truth: people don’t change in isolation from context. [Ref-14]

It can be relieving to realize that “not sticking with programs” is often a coherence problem, not a personal defect. When the loop doesn’t close—when the change doesn’t become self-relevant—your system does what systems do: it conserves energy and returns to what’s familiar.

Programs can absolutely help, especially when they create supportive structure and accountability that respect autonomy and fit the person’s values. But the deepest payoff tends to come when the experience settles into lived identity—when wellness becomes less like a project and more like a stable way of being. And that’s also why many programs show limited long-term gains when they don’t address depth, context, and meaningful engagement. [Ref-15]

From theory to practice — meaning forms when insight meets action.

From Science to Art.

Understanding explains what is happening. Art allows you to feel it—without fixing, judging, or naming. Pause here. Let the images work quietly. Sometimes meaning settles before words do.