Why Silence Feels Unbearable After Constant Noise

For many people, silence doesn’t feel neutral. It can feel like exposure—like something is missing, like time is slipping, like you should fill the space before it fills you. So the hand reaches for a podcast, a video, a message thread, background noise. Not because you’re incapable of being alone with yourself, but because your system has learned that stimulation equals safety.

What if the discomfort isn’t about silence itself—what if it’s about what silence removes?

In a high-input world, quiet can take away the cues that usually keep the day feeling held together: urgency, novelty, updates, and constant micro-confirmations that you’re “in the loop.” When those cues disappear, the nervous system may interpret the gap as a loss of control, and it responds the way it’s designed to respond to uncertainty: by activating.

The fear of silence often shows up as restlessness rather than dread. It can feel like an internal hum, a need to do something, or a subtle sense that you’re falling behind. Silence becomes a blank space your body tries to fill—fast.

This isn’t a character issue. It’s a regulation pattern: when the environment goes quiet, the system scans harder. Without external input, attention turns toward internal sensations, unfinished tasks, and unresolved loops that were temporarily muted by noise.

In other words: silence can expose load that was already there. [Ref-1]

When days are filled with steady inputs—alerts, music, feeds, conversations, metrics—the nervous system adapts. It begins to expect a certain level of stimulation as the baseline. In that baseline, you may feel oriented: time has structure, the mind has something to track, and the body receives constant “something is happening” signals.

Silence removes those signals abruptly. And the brain doesn’t always label that as rest. It may label it as uncertainty. Uncertainty is a classic trigger for threat circuitry: it increases monitoring, prediction, and readiness. The discomfort can be less about “being alone with your thoughts” and more about the system losing its usual scaffolding. [Ref-2]

When your day has been held together by input, quiet can feel like the floor dropping out—even if nothing is actually wrong.

Humans didn’t evolve in silent bedrooms with locked doors and predictable mornings. In many ancestral settings, sudden quiet could mean a change in the environment: the birds stopped, the group got still, the wind shifted—something might be near.

So our systems carry a bias: when the soundscape changes, increase vigilance. That bias isn’t always conscious, and it doesn’t require a specific worry. It’s a body-level “readying” that can be triggered by quiet itself, especially if the nervous system is already carrying high load. [Ref-3]

In modern life, the “danger” is rarely a predator. But the circuitry still does its job: it mobilizes attention, tightens focus, and searches for what needs handling.

Noise, content, and activity don’t just entertain—they can function as safety cues. A playing video can make a room feel inhabited. A podcast can make a commute feel accompanied. Notifications can make you feel connected to a wider net of meaning.

Stimulation also provides quick closure signals: a new clip starts, a message arrives, a headline resolves into an opinion. Even when the content is stressful, the predictability of input can feel oddly steadying.

This is why silence can feel like standing in an unlit hallway. The mind isn’t necessarily “afraid of feelings.” It’s responding to the removal of a stabilizing structure—one that has been doing regulatory work in the background. [Ref-4]

There’s a difference between relief and recovery. Stimulation can bring relief by shifting state—distracting, engaging, speeding up, smoothing over. But recovery is what happens when the system receives enough safety to stand down.

Silence is one of the conditions that can allow that stand-down. Not because silence is inherently virtuous, but because reduced input lowers the processing demand. In quieter conditions, the body gets a chance to recalibrate baseline arousal, digestion, and sleep-wake rhythms.

The paradox is that the very environment that supports recovery can feel uncomfortable at first—because it removes the tools that were helping you cope with overload. [Ref-5]

Silence sensitivity often stabilizes through a simple loop. Quiet appears. Discomfort rises. Stimulation is added. Relief arrives. The brain records the sequence: quiet was the problem; input was the solution.

Over time, this can narrow the system’s tolerance window for low-input states. It’s not that you “can’t handle silence.” It’s that silence has been repeatedly paired with an activation spike and then quickly overwritten by relief.

What gets reinforced isn’t weakness—it’s association.

And because relief is immediate, the loop gets strong even when the long-term cost is fatigue, fragmented attention, and sleep disruption. [Ref-6]

Silence avoidance is often subtle and socially normal. It can be built into routines so seamlessly that it doesn’t register as a pattern—until the moment the sound stops.

These are not irrational behaviors. They are attempts to keep the system regulated with the tools available—especially when life doesn’t offer many natural completion points.

The more constant the input, the less often the nervous system gets to practice “nothing is happening and that’s okay.” [Ref-7]

Quiet is where many processes finish. Not in a dramatic, emotional way—but in a physiological way: stress chemistry clears, attention stops hunting, and the body receives the message that the environment is stable enough to downshift.

When silence is consistently replaced with input, those completion cycles can stay partial. The system remains in a semi-on state: not fully distressed, but not fully settled. This can look like light sleep, persistent mental chatter, and a sense that your day never quite ends.

Importantly, this isn’t about “processing feelings” as a project. It’s about allowing the nervous system to receive enough low-demand time for signals to return to baseline and for experiences to register as done.

In many nervous systems, regulation is less about adding techniques and more about removing constant demand long enough for recovery to occur. [Ref-8]

Tolerance is shaped by exposure, but also by physiology. If the body rarely gets low-input conditions, it can start to treat low input as unusual—and unusual can read as unsafe.

Meanwhile, frequent stimulation keeps reward and attention systems highly engaged. The contrast effect grows: normal quiet feels flat, and flat can be misread as wrong. That misread can create a feedback loop where silence feels increasingly intolerable, even if nothing new has happened in your life.

So the pattern isn’t “you’re getting worse.” It’s a predictable outcome of repeated state-shifting without enough completion. The system becomes trained to expect constant signal.

Even healthy activities can interact with dopamine-linked systems and perceived mood/drive, shaping what “normal” feels like over time. [Ref-9]

Many people assume the goal of quiet is to feel instantly calm. But calm is a state, and chasing states can keep the system in performance mode. Safety is different: it’s the gradual learning that nothing needs to happen right now.

In restoration, the nervous system often passes through transitional sensations—restlessness, boredom, mental noise—before it finds a steadier baseline. That doesn’t mean silence is harming you. It may mean your system is metabolizing load and recalibrating expectations after prolonged input.

In neuroscience terms, fatigue and regulation are closely linked to neurotransmission and sustained demand; removing demand can initially reveal how taxed the system has been. [Ref-10]

Silence isn’t a test you pass. It’s a signal your body learns to interpret differently once it has enough closure.

Humans are social regulators. For many nervous systems, safety is amplified by co-presence: another steady body nearby, a shared space, a sense of “we’re okay.” In that context, silence can be less ambiguous.

This isn’t about needing someone to rescue you from your mind. It’s about how the brain’s threat and reward circuits respond to relational cues—tone, proximity, predictability, belonging. When those cues are available, the system can downshift more easily because it doesn’t have to monitor alone. [Ref-11]

That’s why some people can sit quietly with a friend, partner, or even in a quiet public place, but feel activated in silence at home. The variable isn’t strength. It’s safety context.

When silence becomes more tolerable, the change is often subtle. It’s not necessarily a rush of peace. It’s more like the body stops bracing. The mind stops scanning for the next thing. Time feels less jagged.

People often describe an increased capacity for simple signals: hunger and fullness returning, clearer fatigue cues, easier transitions into sleep, less urgency to “fix” the moment. The system starts receiving “done” messages again.

This shift also relates to motivation and fatigue: when behavior is driven mainly by pressure and constant external prompts, mental fatigue can rise; when actions feel internally coherent and less forced, fatigue dynamics can change. [Ref-12]

Coherence feels like less chasing—not more effort.

In a high-reward, high-velocity environment, attention is repeatedly pulled outward: more information, more novelty, more signal. Silence reverses that direction. It becomes a space where attention can reorient to what matters, what’s unfinished, and what’s actually needed.

That can feel uncomfortable at first because it highlights misalignment: a life that’s been managed through stimulation may not have many natural endpoints. Silence doesn’t create the misalignment—it reveals it.

Over time, quiet can become less like deprivation and more like orientation. A place where reward systems aren’t constantly hijacked, and where the body can sense what is satisfying versus merely activating. This matters in a culture where reward responses can become misaligned with healthful behavior. [Ref-13]

If silence has felt uncomfortable, it doesn’t mean you’re broken or “too sensitive.” It often means your nervous system has been doing a lot of work for a long time—tracking, responding, staying ready—and quiet removes the scaffolding it relied on.

From a meaning perspective, constant input can keep life from landing. Silence is one of the places where experiences can finally register as complete, where the day can feel like it has edges, and where identity can feel less like a performance and more like a settled continuity.

In that sense, silence isn’t a void. It’s a signal: conditions are safe enough to stop scanning. And in modern environments built to keep attention engaged, remembering what “safe enough” feels like can be a profound form of agency. [Ref-14]

When silence stops reading as threat, it often reveals something simple: you were never failing at stillness. Your system was carrying load without enough closure.

Quiet can become less of a confrontation and more of a companionable backdrop—where your attention isn’t being pulled apart, and where your life can start to feel more integrated from the inside. What shows up there isn’t always comfortable, but it’s often clarifying: a truer sense of what’s complete, what’s calling for resolution, and what’s genuinely yours. [Ref-15]

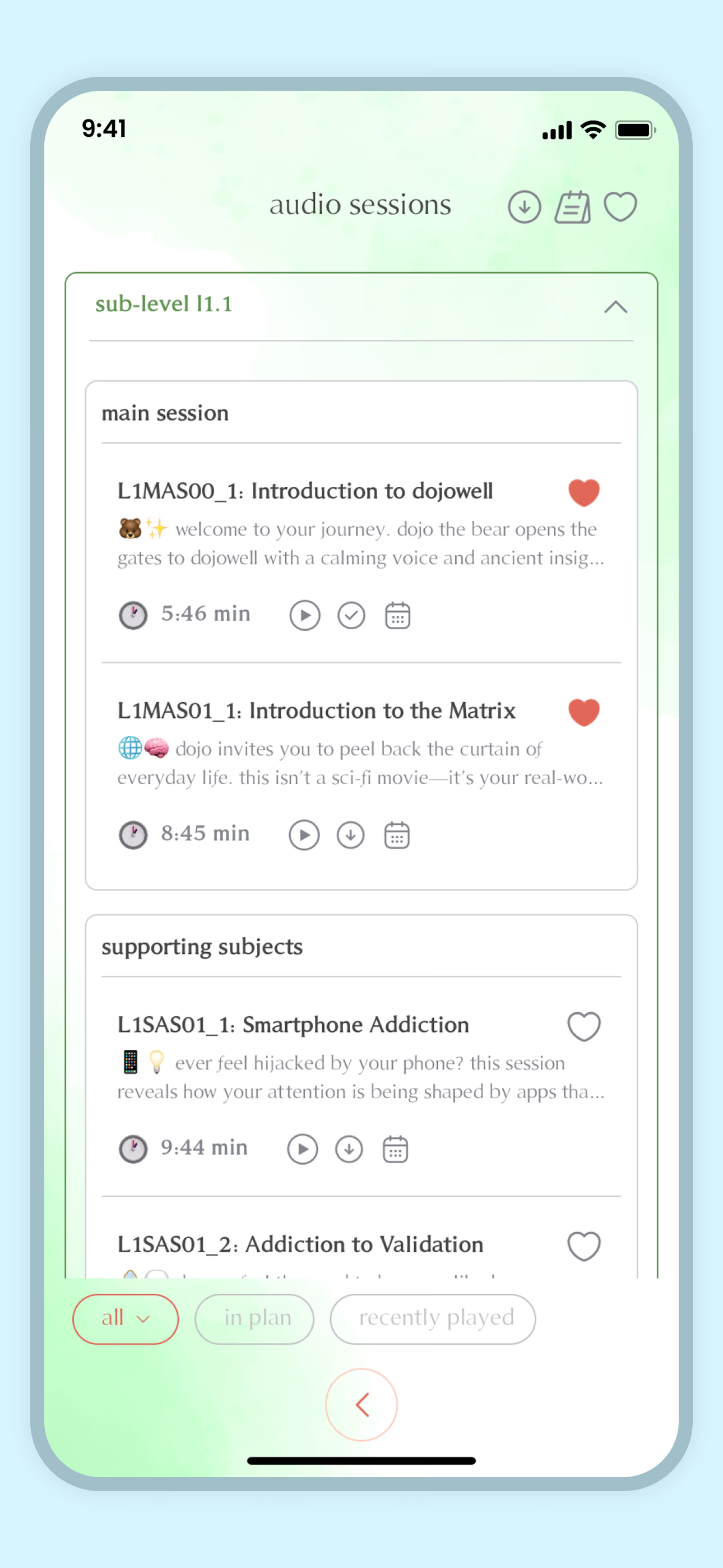

From theory to practice — meaning forms when insight meets action.

From Science to Art.

Understanding explains what is happening. Art allows you to feel it—without fixing, judging, or naming. Pause here. Let the images work quietly. Sometimes meaning settles before words do.