The Myth of Hustle Energy: Why You Crash Later

Remote work can look like freedom on paper: no commute, more control, fewer interruptions. But many people discover a quieter tradeoff—work starts to leak into everything, and the day never fully resolves.

Why does your brain keep checking work even when you’re technically finished?

Boundary collapse isn’t a personal failure of discipline. It’s what happens when the cues that normally separate effort from recovery fade, and your system stays partially activated to keep track of what’s unfinished.

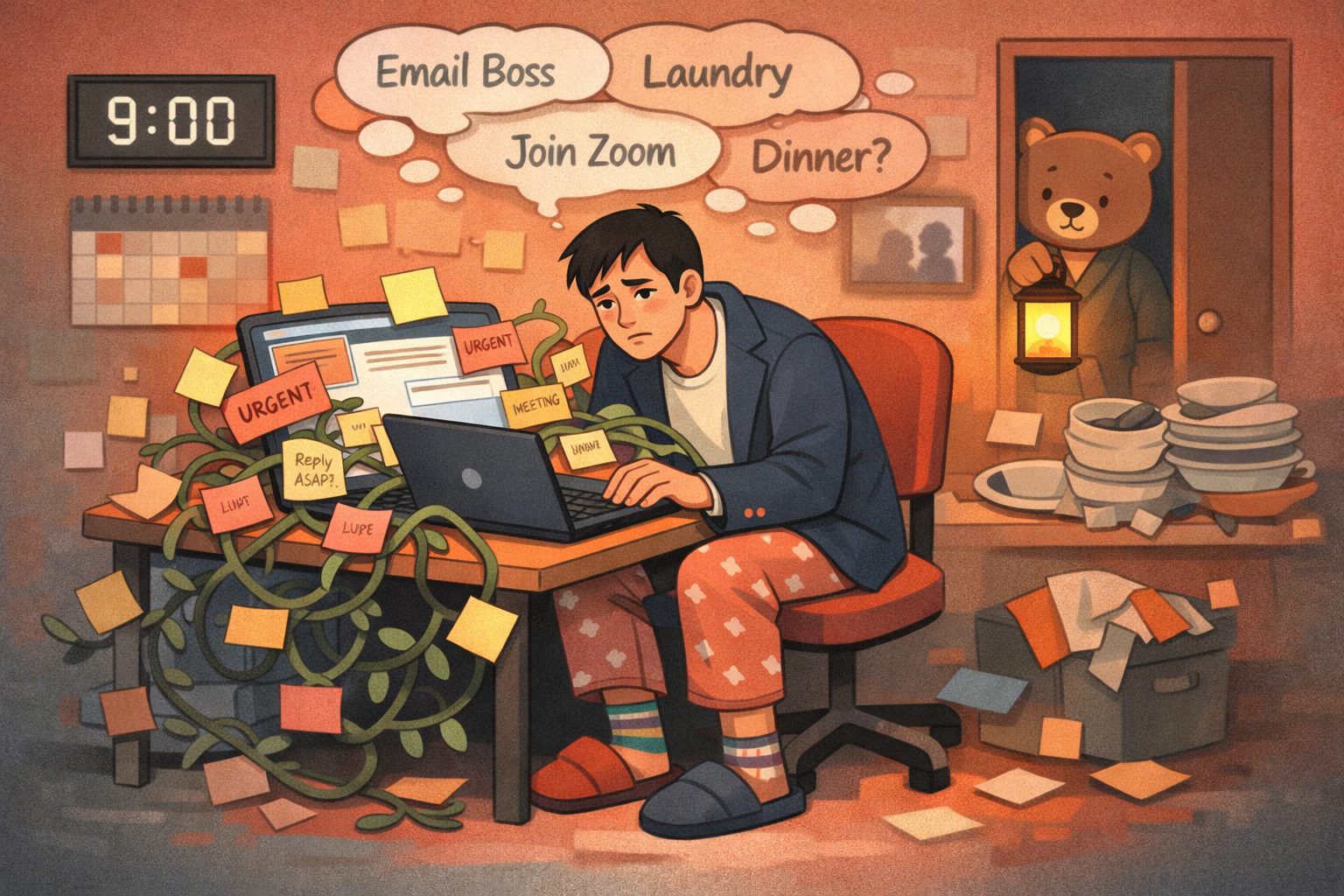

In boundary collapse, the problem often isn’t that you keep working. It’s that work keeps existing in the background: messages that could arrive, tasks that might be judged, tabs that imply responsibility, and a mental list that never quite clears. [Ref-1]

Your mind may keep doing small, low-level scans—checking email “just in case,” revisiting a to-do list, rehearsing tomorrow’s meeting—because there wasn’t a clear moment of completion. Without that completion, the system keeps a little energy allocated, like leaving a burner on low so it’s ready.

When work is everywhere, your attention can’t tell when it’s safe to stop tracking it.

Humans don’t shift from effort to rest purely by decision. We shift through context: where we are, what we’re wearing, what time it is, what sounds are present, what other people are doing. Those cues help the brain predict what’s required next—and allocate energy accordingly. [Ref-2]

When the same space holds work, rest, social connection, and sleep, the predictions blur. The nervous system stays partly mobilized because it can’t fully rule out demands. This can look like “relaxing” while still bracing, or “resting” while mentally tracking work in parallel.

For most of human history, tasks had natural boundaries. There were distinct places and times for effort, and distinct places and times for downshifting—often supported by other people. Those separations weren’t luxury; they were regulatory infrastructure.

Remote work can remove some stressors while also removing the built-in transitions that help completion land in the body: leaving a site, walking home, changing clothes, seeing different faces, entering a different social rhythm. When those transitions disappear, the brain has less evidence that the “work chapter” has ended. [Ref-3]

Always-on behavior often starts as a practical adaptation. If expectations feel unclear, responsiveness can temporarily reduce ambiguity: you’re less likely to miss something, less likely to be perceived as absent, less likely to fall behind. In the short term, it can create a sense of control. [Ref-4]

But the tradeoff is that the system never gets the clean drop in demand that tells it to stand down. Availability becomes a substitute for closure: instead of finishing, the mind stays “ready.” Over time, readiness begins to feel like a requirement rather than a choice.

Flexibility is real—and for many people, it’s genuinely supportive. The mismatch happens when flexibility also means porous time, variable expectations, and work that can be continued indefinitely. The day stops having a natural end point, because the work is never fully “contained.” [Ref-5]

Instead of one solid block of effort followed by recovery, the brain is asked to switch states repeatedly: a message during lunch, a quick task after dinner, a meeting squeezed between personal obligations. Frequent state-switching increases cognitive load, even when each piece is small.

What if the exhaustion isn’t from working too much, but from never fully exiting “work mode”?

One way to understand boundary collapse is as a loop built from incomplete endings. When tasks don’t reach a clear stopping point, the system compensates by keeping them mentally “available.” That availability can feel like vigilance, but structurally it’s just tracking—keeping open loops from being lost. [Ref-6]

This is why disengaging can feel strangely difficult even when you want rest. The mind isn’t necessarily driven by emotion or lack of desire; it’s responding to unfinishedness. Without closure, attention stays partially allocated, which reduces recovery, which then lowers capacity, which makes closure harder. The loop tightens.

Boundary collapse often shows up as patterns that look like “poor habits,” but are better understood as regulation under load—ways the system tries to keep up when completion is missing.

These patterns can be especially strong when work is evaluative (performance pressure), invisible (no clear “done”), or socially ambiguous (unclear response expectations). [Ref-7]

Over time, living without clear endings can produce a particular kind of depletion: not just tiredness, but reduced signal return. Focus dulls. Pleasure feels less available. The mind reaches for stimulation or control because those states are easier to generate than genuine restoration. [Ref-8]

This is one pathway into burnout-like experiences in remote work: not necessarily because each day contains extreme effort, but because recovery is interrupted by ongoing cognitive engagement—anticipation, checking, and the sense that something might still be required.

People sometimes describe emotional blunting here, not as a deep inner issue, but as a nervous system economy measure: when activation is chronic, sensitivity gets turned down to conserve resources.

Remote work can make responsiveness feel like social proof. When teammates are invisible, the system looks for other cues of connection and safety—being quick to reply, staying reachable, signaling presence. If you’ve ever felt that silence might be misread, you’re not alone. [Ref-9]

In that context, always-on behavior isn’t just about tasks. It’s also about maintaining relational continuity: showing you’re still in the group, still reliable, still engaged. The irony is that constant availability can crowd out the very rituals that would restore clarity and steadiness—because the day never fully closes.

It can help to separate two things: understanding what’s happening, and having your system actually settle. Insight can name the pattern, but the nervous system downshifts when it receives convincing evidence of completion—an ending that lands, not just an explanation. [Ref-10]

Closure is not a motivational concept. It’s a physiological one: fewer open loops to track, fewer pending cues to interpret, fewer micro-demands competing for priority. When the environment (and the social field around work) provides real endings, attention can release without having to be forced.

Relief changes how you feel for a moment. Completion changes what your system has to carry.

Boundary collapse is often treated as an individual time-management problem, but many of its drivers are social and structural: unclear response times, inconsistent practices across a team, or a culture where being reachable is quietly rewarded. Shared norms reduce the need for constant interpretation. [Ref-11]

When expectations are explicit—when there is a recognizable “off,” a stable rhythm, and fewer surprise channels—people spend less energy scanning for what might be required. That lowers cognitive demand even if the workload stays the same, because the mind isn’t constantly guessing.

When boundaries return, people often notice changes that are less dramatic than “feeling great,” but more important: mental space reappears. Thoughts become less sticky. Rest starts to look like actual downregulation rather than exhausted scrolling. Focus returns because attention is no longer split between the present and a hovering list of unfinished items. [Ref-12]

In a coherent state, it’s easier to sense what matters and what can wait. Not because you’re trying harder, but because fewer competing signals are demanding equal priority. The nervous system has more capacity for signal return—subtle cues of hunger, fatigue, satisfaction, interest, and completion.

Not “perfect balance”—just clearer chapters.

One of the deepest costs of boundary collapse is identity diffusion: when work is everywhere, it can start to feel like you are never fully elsewhere. Life becomes a series of half-presences—half working, half resting, half connecting.

When work is structured as a bounded chapter, it becomes easier to relate to it with steadiness. Effort has a beginning and an ending; responsibility has a container; your non-work self isn’t merely “time off,” but a real domain with its own coherence and dignity. This is less about rigid separation and more about preventing endless spillover. [Ref-13]

Interestingly, many reports of remote-work strain aren’t about disliking remote work itself—they’re about disliking the feeling that the day never resolves. Clear edges make work feel like a part of life again, instead of the air life breathes.

Boundaries are often framed as a personal preference, but they also function as biological and narrative containers. They help the nervous system recognize when demand is over, and they protect the parts of life where meaning consolidates: meals, relationships, solitude, sleep, unstructured thought. [Ref-14]

When those containers thin out, people don’t lose character—they lose coherence. And when coherence is reduced, the system compensates with tracking, urgency, and keeping options open. Seeing boundary collapse this way can replace shame with orientation: this is a predictable response to an environment without endings.

Remote work can expand possibility, but human systems still need completion. Without real endings, attention keeps paying rent to unfinished tasks, and life starts to feel like an open office you can’t leave.

What restores stability is not more pressure, more self-monitoring, or better self-critique. It’s the presence of enough closure—enough contained chapters—that your system can finally stand down and return capacity to the rest of who you are. [Ref-15]

From theory to practice — meaning forms when insight meets action.

From Science to Art.

Understanding explains what is happening. Art allows you to feel it—without fixing, judging, or naming. Pause here. Let the images work quietly. Sometimes meaning settles before words do.