Remote Work Boundary Collapse: Why You Can’t “Turn Off”

Work–life balance is often described like a clean equation: a stable split between “work time” and “life time,” with clear borders and predictable handoffs. That picture made more sense in a world with fewer channels, fewer pings, and more shared rhythms—commutes, closing hours, and social norms that signaled when one role ended and another began.

Modern life doesn’t cooperate with that model. Many people aren’t failing at balance; they’re navigating a system that keeps roles partially open all the time. Work follows you. Home follows you. And the nervous system keeps registering “not done” on multiple fronts.

What if the problem isn’t your effort—but the way “balance” assumes separation that life no longer provides?

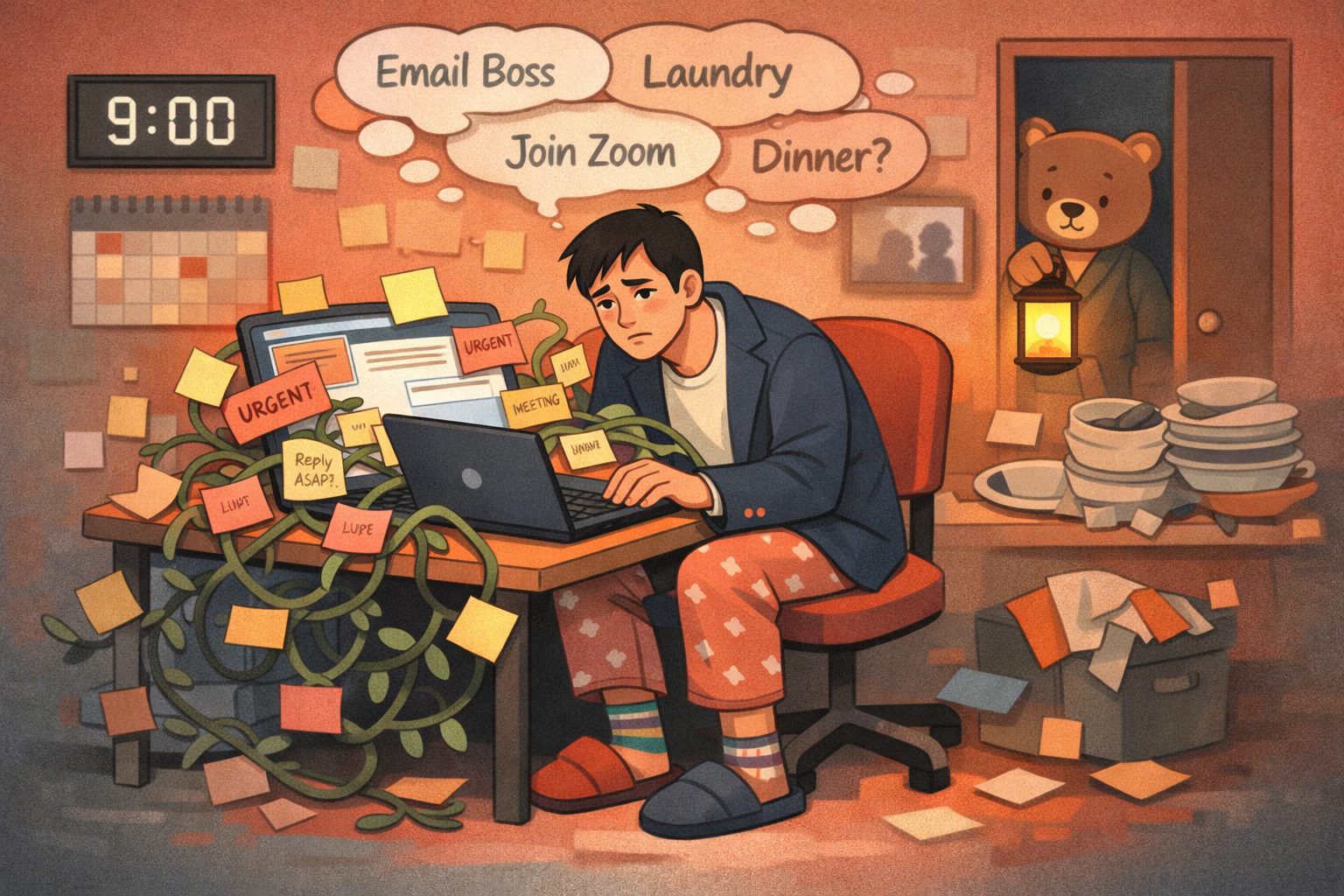

A common experience under the work–life balance ideal is chronic guilt: when you’re working, you feel you should be present at home; when you’re at home, you feel you should be working. The emotional flavor can look like self-criticism, but structurally it’s often a lack of closure—two lanes of responsibility running at the same time.

This is amplified by “ideal worker” expectations (always available, always responsive) colliding with “ideal caregiver/partner/friend” expectations (always attentive, always emotionally present). When both ideals stay switched on, the system experiences constant discrepancy: no moment fully matches what it “should” be. [Ref-1]

It can feel like you’re living in two places at once—and doing a poor job in both.

Even without a dramatic crisis, frequent switching between roles—employee, parent, partner, adult child, friend, household manager—creates micro-demands. Each demand is small, but each one requires an orientation shift: different language, different priorities, different consequences. That ongoing switching can keep the nervous system mildly activated, like an engine that never fully idles.

Research on work–family conflict describes it as a chronic stressor linked to exhaustion and strain, not because any single task is impossible, but because competing demands reduce recovery windows. The body doesn’t just need breaks in time; it needs moments where the “open tabs” actually close. [Ref-2]

When do you get a true “done signal” anymore?

Across most of human history, effort came in cycles. There were intense periods (hunting, harvesting, protecting) and then real downshifts (darkness, seasonal slowing, communal rest). Those rhythms weren’t perfect, but they offered completion: tasks ended, and the environment reliably signaled “stand down.”

When effort becomes continuous partial engagement—some work, some home, some social obligation, some self-management all day—the body can lose the sense of phase change. Without phase change, recovery becomes harder to access, even when you technically have “free time.” Studies linking work–family conflict to stress and health concerns highlight this cumulative load effect. [Ref-3]

The promise of balance offers something deeply human: a sense that harmony is achievable if you can just find the right arrangement. It implies control. It implies fairness. It suggests that discomfort means you haven’t discovered the correct system yet.

But when the underlying conditions are conflicting—roles that compete for the same hours, attention, and energy—“balance” can turn into a pressure story. You may keep adjusting and still feel strain, because the strain isn’t only inside you; it’s in the collision between demands. Work–family conflict research consistently shows that incompatible role pressures predict distress and burnout. [Ref-4]

It’s easy to treat work–life balance like a personal engineering project: rearrange the calendar, fix the morning routine, improve the handoff, become more consistent. But many lives are fragmented by design—multiple income streams, caregiving without backup, unpredictable schedules, global teams, constant accessibility, and the quiet expectation that everyone will “figure it out.”

When life is structurally fragmented, the goal of equal distribution becomes less realistic. What grows instead is conflict: not just between work and family, but between time blocks that can’t carry the meaning they’re supposed to carry. Research on working parents shows that work–family conflict is associated with anxiety, especially under health and caregiving pressures. [Ref-5]

In a fragmented life, the issue is often not effort—it’s collision.

In an overload situation, the mind often reaches for an explanation that feels actionable. “If I were better at balance, this wouldn’t feel so bad.” That story can be compelling because it keeps the problem small and personal—something you can carry alone.

But self-blame can function like an Avoidance Loop: it absorbs the nervous system’s discomfort without requiring you to fully register the larger reality of too-many-demands and too-few supports. In other words, guilt can become a decoy task—endlessly processed, never completed—while the underlying load stays the same. Reports on work–life balance in different regions repeatedly point to cultural and structural barriers that individuals cannot simply out-discipline. [Ref-6]

When the system is too heavy, the brain often tries to make it your fault—because “my fault” feels simpler than “this is bigger than me.”

When balance is treated as a clean separation, many people end up with a predictable set of patterns. These are not character flaws; they’re regulatory responses in a context that keeps roles open and consequences muted until they stack.

These patterns are often the nervous system trying to manage unfinished loops: keep scanning, keep catching up, keep holding everything at once.

When roles stay open and recovery stays incomplete, the body adapts. At first, adaptation can look like powering through. Later, it may look like burnout, resentment, or a kind of flattening—less spontaneous presence, less signal return, more effort to access what used to be natural.

Some people describe a dullness around both work and home: not because they don’t care, but because caring without closure is expensive. Others notice irritability or detachment, which can be the system’s way of reducing input when it cannot reduce demands. Many writers and researchers now argue that “balance” is the wrong frame, and that integration or harmony better matches real human functioning under modern conditions. [Ref-8]

Burnout isn’t only about doing too much—it’s also about never arriving.

Modern productivity culture reinforces a particular hope: that better balance is always one more tweak away. A new app, a new system, a new boundary script, a new self-management identity. The underlying message is subtle: if you still feel strained, you haven’t optimized correctly.

This keeps the nervous system on a treadmill of adjustment without completion. The goalpost moves because the environment moves: new expectations, new metrics, new comparison points, new visibility. In that climate, “balance” becomes a mirage—something you chase while staying continually activated. Many cultural analyses now describe work–life balance as obsolete not because people don’t need relief, but because the conditions that made balance possible have changed. [Ref-9]

There’s an important distinction between relief and stability. Relief can come from a pause, a treat, a weekend, a brief escape from demands. Stability comes when life provides more closure—when fewer roles remain partially open, and when the system can trust that “done” is real.

Seen this way, the struggle isn’t that you can’t maintain an ideal schedule. It’s that modern life often prevents completion. Tasks leak across domains. Communication never fully ends. Standards stay ambiguous. The nervous system responds by staying ready, and readiness feels like tension. Many contemporary discussions of work–life balance describe it as a mirage precisely because the conditions for clean separation are no longer reliable. [Ref-10]

Harmony isn’t a perfect split. It’s when your life stops leaving you half-in, half-out all day.

Because the pressure is often structural, the softening is often relational and collective. When expectations are shared—within a household, a team, a culture—there is more social permission for roles to close. Closure becomes more available when it’s not something you have to defend alone.

This is one reason “productivity guilt” can be so sticky: it’s not only internal; it’s shaped by visibility, metrics, and the sense of being evaluated even when no one is speaking. When organizations and communities treat constant availability as normal, people absorb that norm as a bodily readiness state. Naming this socially can reduce the sense that your strain is a private inadequacy. [Ref-11]

Many people expect that the path to harmony is more effort: better focus, stronger discipline, more motivation. But often the first noticeable change is simpler and more physiological: guilt softens, and with less internal pressure, attention becomes easier to inhabit.

This isn’t a dramatic emotional breakthrough. It’s a shift in load and closure. When demands are more coherent—or when the story about them becomes less self-blaming—energy stops leaking into constant self-monitoring. You may notice more stable capacity: fewer spikes of urgency, less “background panic,” more ability to be where you are without running an invisible audit. Cultural discussions of work guilt note how deeply internalized productivity norms can make rest feel illegitimate, even when the body needs it. [Ref-12]

“Balance” suggests equal slices. Real life is rarely equal—and many meaningful lives are intentionally uneven. There are seasons of building, seasons of caregiving, seasons of recovery, seasons of learning, seasons of simply getting through. Harmony is the sense that these seasons still belong to the same life, rather than competing lives that never reconcile.

Values help here not as motivation, but as orientation. When actions line up with what you recognize as important, the system can settle because it can make sense of tradeoffs. Instead of constantly asking “Am I failing?” the deeper question becomes “Does this season fit the life I’m living?” Contemporary reporting on work–life strain increasingly points toward realistic harmony—flexible, context-aware, and humane—rather than a perfect split. [Ref-13]

A coherent life doesn’t always look balanced. It looks like it belongs to you.

It can be a relief to consider that work–life balance is not a personal test you keep failing. For many people, it’s an outdated cultural ideal applied to a world that no longer offers clean edges.

Harmony is a different concept. It acknowledges changing capacity, real constraints, and the need for closure—moments where roles can actually end rather than bleed into each other. In this frame, agency isn’t about forcing a perfect arrangement; it’s about making sense of your life as it is, and recognizing what pressures are truly yours to carry. [Ref-14]

If you feel “out of balance,” it doesn’t automatically mean you’re doing life wrong. It may mean your nervous system is responding appropriately to a world that rarely grants completion, and to roles that are designed to overlap.

Many people find that the deepest exhale comes not from perfect boundaries, but from a life that feels more integrated—where responsibilities have clearer endings, where tradeoffs are understandable, and where your days add up to a recognizable identity. Not balanced. Coherent. [Ref-15]

From theory to practice — meaning forms when insight meets action.

From Science to Art.

Understanding explains what is happening. Art allows you to feel it—without fixing, judging, or naming. Pause here. Let the images work quietly. Sometimes meaning settles before words do.