Remote Work Boundary Collapse: Why You Can’t “Turn Off”

Remote work can be a genuine relief: fewer commutes, more autonomy, quieter focus. And yet many people notice an unexpected underside—an ambient loneliness that doesn’t match the amount of contact they technically have. Messages, meetings, and group chats keep flowing, but something still feels unanchored.

This isn’t a personal flaw or a failure to be grateful. It’s often what happens when a social nervous system is asked to run on low-bandwidth cues for long stretches. Humans can stay functional this way for a while—especially when work is busy—without receiving the “we’re okay together” signals that help the body stand down.

How can you feel socially “in touch” all day and still feel alone at night?

Remote work can create a specific kind of solitude: you’re reachable, responsive, and seen on a screen—yet you move through hours without the small confirmations that usually come from shared space. No hallway nod, no shared laugh that isn’t scheduled, no sense that your day is unfolding alongside other human days.

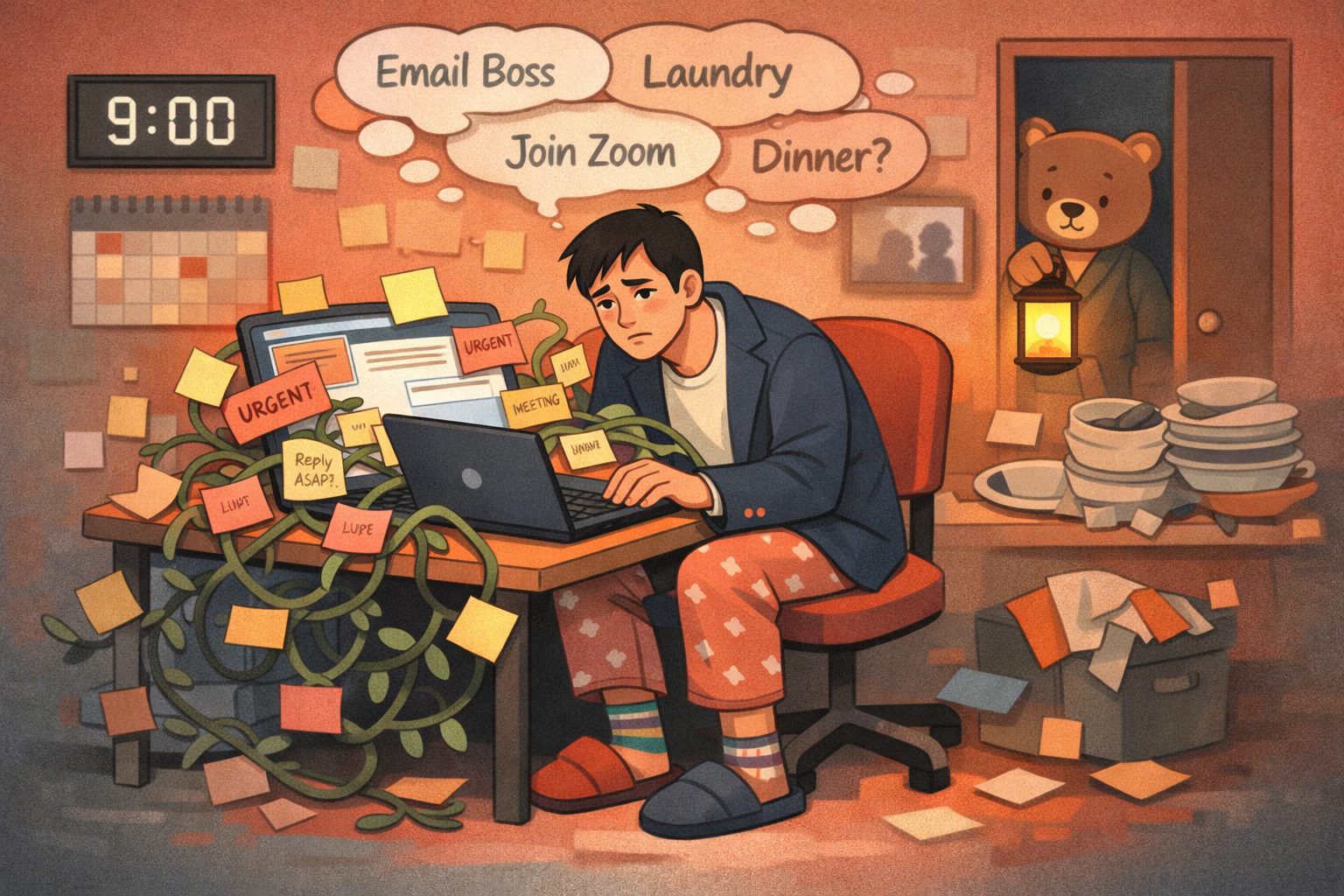

Because the mind can count interactions, it’s easy to second-guess the experience: “I talked to people all day.” But the body doesn’t tally messages; it tracks signals. And when the signals that indicate belonging are thin, the system can register the day as socially incomplete. [Ref-1]

It can feel like you worked with people all day, but lived beside no one.

Human regulation relies on more than words. In shared physical space, the nervous system picks up micro-cues: proximity, posture shifts, breathing pace, eye contact that isn’t mediated, and the subtle predictability of shared rhythm. These cues communicate “safe enough” without needing to be consciously interpreted.

On a screen, many of these signals are flattened, delayed, or missing. Even with video on, the body is still reading: limited depth, limited peripheral information, limited sense of coordinated movement. Over time, this can create a mismatch—cognitive social contact without physiological settling. [Ref-2]

It’s not that digital contact is fake; it’s that it’s incomplete at the level the body uses to relax.

Humans are social mammals. Across development and adulthood, stress systems tend to stabilize more easily when there’s reliable, nearby connection—what researchers often describe as “social buffering.” [Ref-3]

This buffering isn’t primarily about deep conversation. It’s often about shared ordinary life: being in the same room, moving through time together, having small moments of coordination and repair. These moments generate a “done” signal—an embodied sense that you are part of a group and that the environment is trackable.

When that background co-regulation is available, effort costs less. When it’s absent, the same tasks can require more internal management, even if nothing dramatic is happening.

It matters to name what remote work gives: less commuting stress, more control over sensory inputs, fewer interruptions, and often a better fit for family life or health needs. These are not small gains. For many people, remote work reduces daily overload and restores capacity in important ways.

It can also reduce the social friction of workplaces: forced small talk, constant visibility, and the subtle pressure of being evaluated. In the short term, that relief can feel like safety—because the system finally gets fewer demands and fewer unpredictable interactions.

And yet, relief from friction is not the same thing as receiving belonging cues. These two experiences can coexist: more freedom, and less felt connection. [Ref-4]

Remote life can be saturated with “touchpoints”: notifications, check-ins, quick replies, and calendar blocks. But belonging is not simply frequency of interaction; it’s the sense of being held inside a shared context—where your presence matters even when you’re not producing output.

In embodied groups, nervous systems often synchronize through shared rhythm: meals, breaks, commutes, laughter, even shared silence. Those rhythms can support stress recovery and bonding chemistry that is strongly linked with social contact. [Ref-5]

Remote work can quietly tilt life toward an “avoidance loop”—not because someone is afraid or broken, but because the environment makes it easy to bypass friction. If a moment might be awkward, effortful, or time-consuming, there’s usually a streamlined alternative: email instead of stopping by, chat instead of walking together, a quick emoji instead of shared nuance.

Efficiency becomes a substitute for completion. The day stays smooth, but fewer social loops fully close. You get the task done without getting the relational “done” signal that tells the system you’re in stable contact.

Over time, permanent connectivity can also keep the system lightly activated—always potentially on-call, always potentially responding—without the clear transitions that tell the body it can fully stand down. [Ref-6]

Disconnection often arrives quietly. Many people don’t notice loneliness as a feeling; they notice it as a change in texture. Social life becomes less reachable. The body conserves. Interest narrows. The day ends and there’s no residue of shared life—just tasks completed.

Common patterns can include:

These aren’t character traits. They can be sensible responses to reduced co-regulation and fewer completed social loops. [Ref-7]

When the social system doesn’t receive steady safety cues, the body may compensate in a few predictable ways: increased vigilance, reduced outward engagement, or a kind of functional numbness that keeps things manageable. None of these are moral failures; they’re load management.

Over time, people can also experience a subtle “identity drift.” Without frequent mirrors from real-world interaction—tone, timing, shared context—your sense of who you are can feel less anchored. The result isn’t necessarily sadness; it can be a vague unreality, like life is happening behind glass.

Research on perceived isolation suggests it can shape cognition and stress physiology, influencing how safe or effortful the world feels. [Ref-8]

Remote work can keep loneliness out of awareness because productivity provides structure, urgency, and measurable closure. Projects finish. Tickets close. Meetings end. The mind gets “done” signals from tasks, even if the social nervous system doesn’t.

This is why many people don’t recognize the cost until there’s a break in momentum—after a deadline, during a holiday, or when energy finally dips. The emptiness can feel sudden, but it’s often delayed information: the system reporting that relational completion has been missing for a while.

Social buffering is one of the ways humans naturally recover from stress; when it’s reduced, the same workload can start to feel heavier and more solitary. [Ref-9]

There’s an important distinction between relief and integration. Relief can come from fewer interruptions, fewer commutes, and fewer demands. Integration is what it feels like when life reliably completes: the body recognizes transitions, relationships have continuity, and the day has a coherent beginning, middle, and end.

Remote work often compresses transitions. Without walking into a place, seeing familiar faces, and leaving at a shared time, the nervous system may not receive clear boundary cues. The day can blur, and the self can blur with it—not because anyone is doing it wrong, but because the environment provides fewer natural “chapter breaks.”

When burnout enters the picture, it’s often less about motivation and more about accumulated load without sufficient stand-down and completion. [Ref-10]

It’s hard to feel grounded in a life that rarely declares itself finished.

Belonging tends to return when interaction becomes more than exchange—it becomes shared time. Physical presence offers a density of cues: coordinated movement, shared attention, and micro-repair when moments are slightly off. These are small completions that tell the nervous system, again and again, “contact is stable.”

Shared rituals also help because they repeat. Repetition creates predictability, and predictability reduces load. Over time, the system learns what to expect and doesn’t need to stay as activated.

Developmental research on social buffering highlights how supportive presence can shape stress regulation; in adulthood, the same principle often applies: being with others in real contexts can reduce the cost of being human. [Ref-11]

When belonging cues become reliable again, people often describe a change that’s quieter than “happiness.” It’s more like steadiness: the ability to rest after effort, the ability to want things again, the sense that life has edges and continuity.

Motivation can return as a byproduct of reduced load—because the system isn’t spending as much energy maintaining vigilance or compensating for missing social completion. Resilience also tends to strengthen when isolation decreases, with meaningful social connection linked to both mental and physical health. [Ref-12]

The deeper issue isn’t whether remote work is “good” or “bad.” It’s whether autonomy is being asked to replace belonging. Freedom without relational grounding can start to feel like floating—lots of choice, not much holding.

When values and identity have real-world continuity, autonomy becomes steadier. It’s no longer solitary self-management; it’s self-direction inside a life that reflects you back. Psychological flexibility research often emphasizes values-based behavior as a stabilizer—less about pushing harder, more about living in alignment with what matters. [Ref-13]

Digital freedom tends to feel better when it’s attached to a human ecosystem.

Remote work disconnection is often a coherence problem, not a personal problem. When the environment reduces embodied cues, the social nervous system may stay slightly activated, and the self can feel less anchored—even with plenty of messages and meetings.

Agency often begins as orientation: recognizing what your system has been missing, and why it makes sense that it would miss it. When life contains more reliable closure and more real connection, the body doesn’t have to work as hard to feel okay in the world. [Ref-14]

Humans can accomplish a lot alone, especially with modern tools. But thriving usually depends on more than access and efficiency. It depends on the steady, embodied signals that say: you’re with others, you matter here, and the day can end.

If digital freedom has started to feel lonely, that doesn’t mean you’re failing at remote work. It may simply mean your social system is doing its job—pointing you back toward the kind of connection that helps stress settle and meaning stay intact. [Ref-15]

From theory to practice — meaning forms when insight meets action.

From Science to Art.

Understanding explains what is happening. Art allows you to feel it—without fixing, judging, or naming. Pause here. Let the images work quietly. Sometimes meaning settles before words do.