The Trap of Emotional Reactivity: When Feelings Hijack Behavior

An emotional spike can be loud on the outside or quiet on the inside. Either way, it often leaves a confusing aftermath: a rush of regret, a heavy “what was that?” feeling, or a drained, buzzy fatigue that doesn’t match what’s happening anymore.

Why does your body keep acting like it’s still in the moment—even after the moment is over?

Reactivity recovery isn’t about becoming a calmer person through effort. It’s the process of your system returning to baseline after it has already mobilized for protection. In that window, what you most need is often not more analysis, but more closure—enough completion for your physiology to receive the “done” signal.

Many people can tolerate the spike itself better than what follows. Afterward, the mind may replay words, facial expressions, or tone. The body may feel shaky, nauseated, tight-chested, or wired-tired. And socially, there can be a sharp drop: embarrassment, confusion, or a sense that you’ve become “too much.”

This is a common human sequence: a protective surge, then a social and metabolic bill. It doesn’t mean you’re broken; it means your nervous system successfully generated power on your behalf, and now it’s looking for confirmation that it can stand down. [Ref-1]

Sometimes the hardest part isn’t what I did. It’s realizing how long it takes to feel like myself again.

In an emotional spike, the brain shifts into rapid threat-processing. Systems built for scanning and quick action take priority, and the parts of the brain responsible for broad context and long-range perspective become less influential for a time. [Ref-2]

That shift is efficient—especially for survival—but it has a side effect: your body may stay activated even after your environment has changed. The event can be over, yet your internal signals still read “not resolved.” This is why people can feel flooded, impulsive, or unusually certain in the moment, and then surprised by themselves later.

After the peak passes, the nervous system doesn’t always return to baseline immediately. It may remain in a heightened state—alert, scanning, sensitive to tone, and ready to re-engage. This isn’t a failure of self-control; it’s an aftereffect of mobilization.

From a biological standpoint, it can be safer to stay “revved” for a while in case the threat returns. That means the body may keep producing stress chemistry and maintaining muscle tension longer than the situation warrants. [Ref-3]

What if the lingering intensity is your system finishing a sequence—not your personality showing its “true colors”?

In many ancestral contexts, danger wasn’t a single clean moment; it was often uncertain, repetitive, and proximity-based. If a conflict happened, it could re-ignite quickly. If a predator appeared, it might still be nearby. In those conditions, immediate calm wasn’t the goal—readiness was. [Ref-4]

This matters today because the body’s time horizon is older than modern expectations. Your rational mind may decide a conversation is over, but your physiology may still be running the “stay prepared” program.

Modern life often resolves externally before it resolves internally. A meeting ends. A text thread goes quiet. A partner walks away. The “event” is done—but your system may still be holding an open loop: unfinished meaning, incomplete repair, or unclear safety.

When closure doesn’t arrive, the body can keep paying attention. Over time, repeated episodes add up as wear-and-tear—an increased background load that makes future spikes easier to trigger and harder to recover from. [Ref-5]

If the aftermath feels uncomfortable enough, many people begin to relate to the spike as something to outrun. Not because they’re “afraid of feelings,” but because the nervous system learns a simple association: spike → long fallout → social or internal cost.

That sets up an avoidance loop where the recovery phase gets bypassed. The mind tries to solve the discomfort by withdrawing, self-criticizing, or over-explaining. Rumination can feel like accountability, but physiologically it often keeps the loop open—more activation without completion. [Ref-6]

In this loop, shame isn’t a personality trait; it’s a regulatory strategy attempting to prevent future spikes by increasing internal pressure.

After reacting more strongly than intended, people often default into patterns that look like responsibility from the inside—but function like continued threat from the body’s perspective.

These responses are understandable. They aim to restore coherence and safety. But self-criticism in particular tends to amplify shame and distress, which can keep the system on alert rather than letting it settle. [Ref-7]

Repeated unrecovered spikes can change how life feels. Not because you’re “getting worse,” but because your baseline load rises. When the system spends more time activated, there’s less room for nuance, patience, and repair.

Over time, this can erode confidence (“I can’t trust myself”), strain relationships (“I’ll just keep to myself”), and reduce resilience (“I can’t handle one more thing”). Attempts to suppress or clamp down may reduce outward expression while increasing internal physiological strain. [Ref-8]

In other words, it’s not only the spike that matters—it’s the recovery debt that accumulates when spikes don’t reach closure.

After a spike, the environment may be quiet—but the inner environment can become hostile. When the internal narrative turns punitive, the nervous system often treats it as more danger: more monitoring, more tension, more urgency to “fix.”

This is one reason “be nicer to yourself” can land flat. The issue isn’t kindness as a concept; it’s that judgment functions as an alarm. Even if it’s meant to improve behavior, it can prolong dysregulation by keeping threat cues online. [Ref-9]

When I start prosecuting myself, my body doesn’t calm down. It braces.

A spike is an upshift—mobilization, speed, narrowed focus. Recovery is the downshift: a physiological transition where arousal decreases and the system begins to re-open access to context, timing, and proportion.

Importantly, downshifting isn’t the same as understanding what happened. Insight can arrive while the body is still activated. Recovery is more like a settling: breathing and heart rate becoming less urgent, muscles releasing, attention widening, and the “watchfulness” dial turning down because enough safety cues are present. [Ref-10]

When downshift happens, it’s not a reward for doing it right. It’s the nervous system recognizing completion—internally, relationally, or situationally.

Humans regulate in connection. Safety is not only an internal state; it’s often a relational signal—tone of voice, facial softness, predictable responses, and the sense that rupture can move toward repair. When those cues are available, the recovery arc is often shorter and less costly. [Ref-11]

Acknowledgment and repair matter here not as moral performance, but as closure mechanisms. They reduce ambiguity. They tell the nervous system, “The situation is not escalating; it’s moving toward resolution.” Co-regulation—being with someone whose system is steadier in that moment—can also provide external structure that helps your physiology find baseline again.

As arousal decreases, many people notice a distinct shift: the world becomes less sharp-edged. Options reappear. Words come more slowly. The impulse to defend, withdraw, or redo the scene begins to fade. This is not simply “a better attitude”—it’s an increase in capacity after load reduces.

Social buffering is one reason this can happen faster in supportive company. The presence of reliable others can dampen stress responses and help the body interpret the moment as safe enough to end. [Ref-12]

In this settled state, meaning can start to consolidate: not as a dramatic emotional release, but as a quieter sense of “I know what happened, and I’m not stuck inside it.”

Over time, the most stabilizing shift is often not “never spike again,” but changing what happens after. Self-punishment keeps the nervous system in threat mode and frames the episode as a permanent indictment. Repair-oriented leadership frames the episode as a temporary state that can be completed.

That leadership isn’t about control; it’s about coherence—actions and values aligning in a way that your body can believe. When repair becomes the organizing principle, identity starts to update: “I’m someone who can come back.” Safety signals—internal and interpersonal—become easier to find, and the baseline becomes more reachable. [Ref-13]

Recovery is the part where I become trustworthy to myself again.

It’s possible to hold responsibility for impact while also recognizing the biology of spikes. Those are not opposing positions. One is about values; the other is about conditions and nervous system load.

When recovery is treated as a normal phase—rather than proof of failure—people often experience a subtle return of agency. Not the pressured kind that comes from force, but the grounded kind that comes from knowing the system can cycle back to baseline. Research on stress and recovery consistently points to the importance of recovery states, not just stress states, in overall functioning and wellbeing. [Ref-14]

In that frame, “calming down” stops being a test of character and becomes a form of closure: the body receiving the message that the loop can end.

The spike is the survival system doing its job in imperfect conditions. The return is where coherence is rebuilt—where experience becomes integrated enough to stop demanding your attention.

Over time, this is how strength tends to look: not a life without activation, but a growing ability to re-enter your values after activation and let your identity be shaped by repair rather than punishment. That kind of flexibility—returning to what matters after disruption—is a durable form of resilience. [Ref-15]

From theory to practice — meaning forms when insight meets action.

From Science to Art.

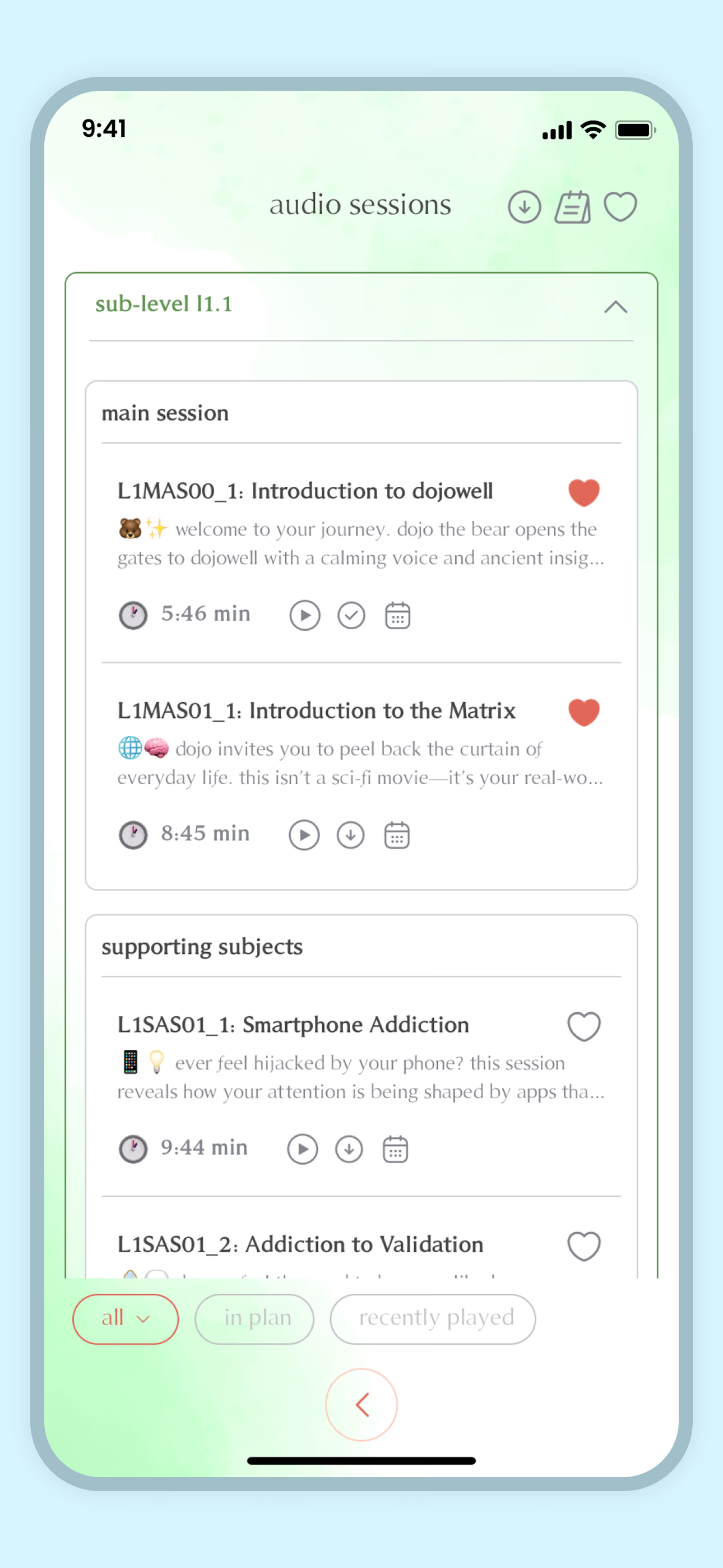

Understanding explains what is happening. Art allows you to feel it—without fixing, judging, or naming. Pause here. Let the images work quietly. Sometimes meaning settles before words do.